Krunislav Stojanovski- Cycles

A Synthesis of Differences as an Ontological Foundation

Krunislav Stojanovski, Twenty Years of Work

“In my art I attempt to explain

life in its meaning to myself”

Edvard Munch

A linear tracing of the dialectic of modern and contemporary fine art has no refuge in the work of the Macedonian-Croatian painter Krunislav Stojanovski. What is paradigmatic of him is the uncompromising/free flow of his desire to incessantly wander through the aesthetic and stylistic preferences of the 20th century. Post-modernist excursions from one to another diametrically opposite shore of stylistic coding of various visual representations are at the heart of the expressive methodology he has chosen. The uninitiated may perhaps react inappropriately to such behaviour, but in order to fully grasp the author’s poetics, one first needs to recognise the fundamental meaning of his work’s nomadically grounded platform. It consists of the unlikely connection of what is defined as purely artistic (art for art’s sake) and that which is called engaged (the artistic in a relationship with reality, with actuality). Hence, jumping to conclusions may lead to such questions as: “How can action painting at the same time designate both an explicitly aesthetic and a genuinely engaged reaction to the traumatic moments of the past or/and the present?” The same also occurs on the Informalist canvases of the Reliefs, Energies or The Kalevala cycles. Where in them is the representational that may point to the painter’s justified engagement (be it political, ethical, environmental or otherwise)? The arguments in favour of the claim that a synthesis of diametrically counter-posed differences is the ontological foundation of this opus are easily discernible in the few actions, interventions and multi-media projects where the author’s political engagement is rather conspicuous (Earth, 1998; Time and Space, 2002; Sell Your Body, 2004; Zoon Politikon – Eye, 2011), as well as in his involvement in the fields of education, exhibition organisation and other social activities. The plethora of various practices bring into correlation the discourses of such autonomous authorities as Edvard Munch, Franz Kafka, Marcel Duchamp, George Orwell with the CoBrA Group, Pierre Alechinsky, Karel Appel, Đuro Seder or Petar Mazev.

*

The above points to difficulties in establishing an ordinary chronology in the development of Krunislav Stojanovski’s visual discourse. As he himself has noted, “My paintings are divided into seven cycles. Almost all of them, in a way, trace their beginnings to the days when I was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (AFA), except for the Meanders cycle, which I began sometime around 2000.” Of all the professors at the AFA, the author has the greatest respect and gives the most credit to the painter Đuro Seder. “He discovered an expressionist in me … Much liberated, I then painted three, four, sometimes even eight paintings a day. For that I have ever since been immensely grateful to Seder,

because I think that when a teacher “opens up” a student, he does the best possible thing one can do in the process of education. In this sense, Seder was a gallant and generous man. I often refer to him as my ‘spiritual father’… I have gained a lot from this relationship, especially in terms of the liberation of my gesture and the confidence of my stroke.”

The Faces Cycle

The cycle Faces began in 1994 at the AFA in Zagreb and continued for years, until the 2013 cycle Portraits. It corresponded with the tragedies from the war situation in former Yugoslavia during the 1990s. In it he extensively used the grammar of engaged expressionism, with bursts of association, with thick paste and a particularly powerful chromatic system. He reflected his every feeling of the moments that deeply troubled him. These are diaries of suffering, of empathy, of the pain and horrors from the sights in the fields of fear. This Munchean scream of the soul “as a study of the soul, that is to say a study of my own self” (Edvard Munch) took him the closest to the neighbourhood of the psychological degradation of human personality, to the narratives dominated by spirits, by hallucinations, by fear turned nightmare. By using graphisms and thick paste sparingly, in his depictions of the FACES he elicits impressive expressions, emotional and sensory states. Lurking from those grotesque physiognomies with bulging eyes and beastly gazes are ironic grins, defiance of death through toothed jaws as the ultimate sign of protest. Stojanovski captures the erosion of consciousness, of the soul, of the heart, of the feeling and of the physique – of the integrally dismantled being – by means of simple gestures of his hand, of quick strokes, by the characters’ caricatures, thereby ignoring the stylistic, aesthetic, genre and, generally, every established code in fine art. The discourse at times culminates in a kind of overemphasised expressiveness approaching ecstasies and vertigo. The oil on canvas paintings of the 1990s Child in War, Horror, Under the Cross, Mother and Child, Mother and Dead Child, Whispering, Fear etc. are more explicitly titled than they are explicit in terms of iconographic depiction.

When, later, in 2013, he once again turned to faces in Portraits, he used an even fiercer visual rhetoric – this time, however, using the techniques of simplification, a handwriting bordering on simplified caricature drawings and on comic book reduction of the depictions.

The Crystals Cycle

“At that time [1994/5] I painted the first Crystal 1 (oil on canvas), as an experiment in combining azure and pastose.” (K. Stojanovski). The cycle saw its confirmation and emphasis during his three-month stay at Helsinki’s Cable Factors Art Centre in Finland. The several surviving works were painted between 1994 and 2003. The manner in which they were produced differs from that of his earlier works by the contrasting of pastose and azure segments, by the colouristic restriction to blue or ochre-orange hues, by the delicate strokes that seem to follow the fragile structure of the crystals.

Also impressive is the juxtaposition of the crystals’ gentle glimmer and the rough remnants of vast explosions, both like inorganic remains of some cosmic turbulences, as if alluding to some genesis of the universe, whose gentle message touches our beliefs in the uniqueness of creation and existence.

The Kalevala Cycle

His stay in Finland gave rise to The Kalevala cycle (1998), inspired by the eponymous collection of fifty Finnish epic poems about the creation and the genesis of the world, which, according to the author, are in no way related to the Euro-Asian myths, but to some other myths from the Pacific. These exciting myths from the faraway land which penetrate K. Stojanovski’s works also profoundly pervade the hallucinogenic and fantastic realms of Munch’s discourse. I refer to Munch’s works Moonlight (1895), Separation (1896), Starry Night (1925), Woman on the Veranda (1945) in particular. As if Krunislav Stojanovski’s father had read him the stories about the spirits, just as Munch’s father had done. The atmosphere of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories flows, with an almost identical intensity, through both painters’ paintings. In contrast to the Norwegian painter’s figurative language, absolutely locked in intimate tragedies and disorders, Stojanovski tells the myths, spurred by individual poems from the epic, with an associative-abstract painting vocabulary, though also in a dark colour register with subtle gleams of light, like Munch in his paintings. He uses acrylic and oil, effects of paint trickling, in which he incorporates non-painting material (sawdust, quartz, sand, canvas etc.). The cycle consists of 25 works, with the potential of being further elaborated. I attribute the link with the great painter to an inescapable feeling of anxiety, uneasiness, frantic resistance or concern about oneself and humanity with arms uplifted in a cry for help. In The Kalevala 16 and The Kalevala 17 matter is stirred in post-apocalyptic convulsions that can be associated with certain oil paintings by Mazev from the 1980s. These take us to the next cycle.

The Energies Cycle

This cycle “came into being around 2003, but it was linked with paintings and experiments from my days at the Academy. The purpose was to bring them back to life in this cycle,” – that is to say, to infuse the paintings’ dead static objects with “mobility” by using two elements: Pollock’s drip painting – his use of drops – and the effect of movement which is created by adding lines as it is done in the art of comic books.” Energies (together with works from the Crystals and The Kalevala cycles, and two other paintings made as tributes to Wassily Kandinsky) were exhibited at his 2006 Zagreb solo exhibition. Their denotation as kinetic, potential or coloured is of small consequence to this cycle’s ultimate definition as an exciting marriage of the relatively static and chiefly dark massive formations and the cobweb-like lines made by delicate drips of varied fibres of colour. The layout of this contrasting play upon the white surface accentuates the refined co-operation of the fragile and of the coarse, of the weighty and the weightless, of their filigree-like aggressiveness and the static vibrations of the voluminous forms. In contrast to the ‘all over’ density of the collision between the planes, lines and the primer in the works of the great Jackson Pollock, Stojanovski clearly shows a desire for peaceful conversation in the paintings’ interiors.

The EARTH cycle

Several works from this cycle were painted between 1995 and 1998. They were a departure from the expressionist aesthetics of his earlier works. They rely on the primary geometric forms, the soft flow of the planes, strokes or linearisms and on the oil colour which the painter treats almost as if it were aquarelle (Fluid, 1995; Bull, 1995; Triangle, 1995; Oval; 1998, Cube, 1998). “…[I]n addition to removing colour with a paintbrush and turpentine, I also applied turpentine in a semi-controlled fashion and then

set it on fire, following the principles of Action Painting; each painting came into being by fire and smoke, as I frequently extinguished the fire and attempted to give the painting’s drawing a desired course. It was only partially possible. With these paintings I wanted to turn the attention to the environmental disaster we live in.” Stojanovski imparts the basic forms with associations from the biosphere (a human, an animal, a plant) because he has always had an interest in biology, having in mind particularly the fact that he has also had training in biotechnology (including molecular biology, genetics and ecology). This delineation comes in a more explicit format in the cycle titled Reliefs.

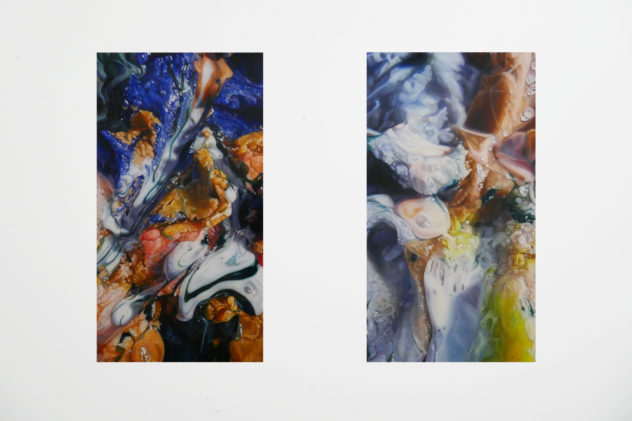

The RELIEFS Cycle

The making of this cycle began around 2007. It too is related to the Earth cycle and the making of certain ambient installations. It encompasses the sub-cycles Red, Violet, Green and White. “The first sub-cycle focuses, above all, on phenomenological issues: how to get a painting with a single dominant colour, without making it simple or minimalist in terms of the stroke and the treatment of the material. They were painted in at least three layers of at least eight to ten different hues of the colour red and its mixtures. This allows the painting to ‘change’ during the course of the day, depending on the nature of the light (i.e. depending on whether the light is natural or artificial), the amount of lighting and the angle at which it hits the canvas. The painting thereby becomes ‘living’, ‘changing’.” The accent on chromaticism or on the monochrome, similarly as in W. Kandinsky, has psychological connotations. Whereas the colour red accentuates the beholder’s most heated turbulences, the colour white brings about the nirvana, the colour green is soothing to the eyes and to the psyche, while the colour violet expands the mysterious dimension of things and their translations in the feelings and senses. Another aesthetic challenge comes from the luxuriant structures, achieved by adding sawdust, canvas, sand, glass and the like. Associative expressionism is the third factor generating these dynamic compositions in which the organic and the inorganic form an eruptive holistic alliance. “The Relief paintings are figural abstractions. In addition to the metaphysical meaning and radiation of the colours and of their combinations, in addition to perception that changes depending on the nature and amount of light that the painting reflects, I also want to hint the sensation of the organic in it – namely, the intentionally added elements that can be felt/seen, despite the different readings that depend on who observes/perceives the painting, are nevertheless associatively organic elements of all that surrounds us and means or can mean Life. Therefore, in those paintings, one can sometimes see an entire submarine world of corals, fish, whales, sometimes existent or non-existent plants, entire jungles of them, but sometimes a micro-world of amebae, cells, micro-organisms, sometimes entire cosmoses complete with planets, suns and milky ways, and yet other times eroticised scenes abundant with phallic or vagina-like shapes, forms in coitus… evincing the richness of the psyche and the personal lives of all of us, evincing the intricateness of our fantasies and private imaginations. These images seek to depict Life itself, or at least a part of it in all its beauty.” (Red Polyptych, Birth Diptych, Violet Diptych, The Violet Saxophone, White Organic).

The MEANDERS Cycle

The Meanders have been coming into being spontaneously, since 2007 until present day, as a subtle combination of the visual texture particular to the wondrous Macedonian carpets and rugs (and other

traditional ethnic motifs) with the geometric regularity of modern-day bar codes. Basically, K. Stojanovski continues to explore in this most recent cycle the magical network of visual riddles in which, like all authors, he always finds material to exploit. “The beginning of Meanders came at a moment of combined circumstances that, through a selection and exploration process, brought about the making of a new cycle around 2008, a cycle on which, as it has been with the other ones, I have been working to this day. It relates to topics that concern me, to various social problems, which I usually address through other media of visual expression, primarily through ambient installations. I wanted to transfer some of them onto the painting medium, intensifying them again as I had done at the outset of the Faces cycle, which had been a critique of war as a means for resolving confrontation, and throughout the Earth cycle, where I had dealt with environmental themes, things relating to our attitude towards our planet.

Something that has always interested me is national tradition, not only Macedonian, but also every tradition that I have come across during my travels. For the installations for the 1998 Earth exhibition, I drew inspiration from the Macedonian, Croatian, and Finnish traditions, as well as from some other motifs that frequently appear among many different peoples throughout the world, having recognised in them the oneness of people, regardless of the place and time they live in, regardless of their nationality, religion or gender. That is how the paintings reminiscent of rugs, or carpets, knitted from scarps of canvas, came about. At a time when I felt an urge to break away from expressionism, which requires vast energy, and to set out for more quiet waters, I was somehow commissioned to produce a painting that would resemble a bar code, a modern detail from a product surrounding us. Wishing to link the traditional (the knitted traditional carpet) and the modern (the bar code), I started a small series of experimental paintings, in which I soon desired to introduce geometric order. Geometry – that is to say, order – though in the manner of the expressive creation which I find the closest to me, had appeared as early as the cycle Spaces, first during my studies around 1995, and later, in fresher colours, around 2004.

When I removed square surfaces from the paintings that had been filled with roughly drawn lines, the meander emerged quite naturally. It is one of the motifs or symbols, which, I think, are printed onto the general human consciousness, along with many other signs, such as the cross, the line, the circle, the swastika, the pentagram, the star, the crescent etc., which have accompanied the rise of civilisation ever since life in caves, but it has also been part of the traditions of India, Ancient Greece or Rome, the Middle East and the Far East, Africa and America, defying both time and space, showing, thereby, the oneness of Man as a being and the equality of people.

Comparing the emergent “multi-coloured” meander with the famed black-and-white meander by the world renowned giant of fine art Julije Knifer, my desire to further explore this field soon arose entirely spontaneously. He had shown the relatedness of the traditional and the contemporary in the best possible of ways, introducing a philosophical element, typical of the thinking of conceptual artists from the mid-Twentieth Century. Declaring that he was “abandoning painting”, and yet expressing himself through the medium of painting itself, but set within a different concept, in which a painting lost meaning as an individual work of art, he made, from today’s perspective, room for others to attempt to find an answer to this conundrum.” Unlike the conceptual discourse of Knifer, who practically declared war on – or rather declared the death of – representative, mimetic painting and assumed the meander as his trademark, K. Stojanovski insists on restoring life to the painting. This position in the narrative exposition is suggestive of the author’s steadfast dedication to maintaining the authenticity and integrity

of both the artwork and the author, to escaping the modern formula called globalisation, which levels difference. This move and idea of K. Stojanovski make the crown of his latest creative preoccupation. “How are we to live in the time that has come to show that this globalisation is not as idyllic as we hoped? There is a need for new individualisation. To me, this re-individualisation of the painting is a symbolic expression of the need for individualisation of Man, a return to oneself and to the place of the individual in our controlled society.” (K.S.)

*K.S. The quotations of the author are borrowed from his notes

Exhibition for Gallery MC organized by Natasa Simovska Poposki